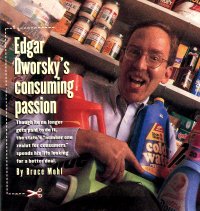

EDGAR DWORSKY'S CONSUMING PASSION

THOUGH EDGAR DWORSKY NO LONGER GETS PAID TO DO IT, THE STATE'S "NUMBER ONE ZEALOT FOR CONSUMERS" SPENDS HIS LIFE LOOKING FOR A BETTER DEAL.

Author(s): Bruce Mohl, Globe Staff

Date: September 27, 1998

Page: 12

Section: Sunday Magazine

As soon as he sees the ad in the morning paper, Edgar Dworsky's consumer antennae start twitching. "Everything in the store is on sale or it's yours for free," screams the full-page ad for a chain store that carries computers, cameras, television sets, software, and stereo components. The language is a challenge Dworsky can't resist. He studies ads the way baseball addicts study box scores, and he knows the state's retail laws and regulations down to the footnotes. Reading the ad again, he combs through the fine print and tries to find the catch, but the store has left itself no loopholes that he can see. Nobody Beats the Wiz is the store's boastful name, but Dworsky thinks he can prove it wrong. A few days later, he cadges a ride to the Saugus store -- Dworsky doesn't drive -- and as he heads toward the entrance, his adrenaline is pumping: He's off to beat the Wiz.

Once inside the big, boxlike store, Dworsky is all business. He marches methodically from consumer electronics to cameras to stereos to TV sets to boomboxes, at each stop looking for items that are marked down, checking the sale price against the original price. Sometimes he does the calculations in his head, sometimes he uses a calculator. Dworsky isn't greedy enough to fill his shopping cart, but he isn't going to walk out empty-handed, either. He selects a digital camera that costs nearly $700. At the checkout counter, Dworsky pays for the items with his credit card and then, with a flourish, produces a copy of the state's regulations that define what is "on sale." Dworsky, it turns out, knows something the Wiz does not: Massachusetts has a very strict definition of a "sale price." When a store does not state the exact savings on a sale, the law assumes that the price will be discounted at least 10 percent on items that normally sell for less than $200. If an item that normally costs more than $200 is labeled "on sale," the law presumes savings of at least 5 percent off the regular price. Nobody Beats the Wiz should have known all this: Dworsky himself, when he was working for the state and the Wiz moved into Massachusetts, had sent the retailer a copy of the state's retailing laws and regulations.

Dworsky patiently explains to the checkout clerk that the camera and camcorder are not "on sale" under the law, since neither has been discounted by 5 percent. Under the terms of the advertisement, therefore, he notes with a voice of quiet authority, he should not have to pay for them. The checkout clerk, looking at him as if he's crazy, calls the assistant manager. The assistant manager has never heard of the law, either, and he's not about to give away $1,300 worth of merchandise to some skinny guy with a mustache who's waving a set of state regulations in his face. So he refers Dworsky to the retailer's home office in New Jersey. After several weeks of haggling, Nobody Beats the Wiz acknowledges that it has been beaten. The camera caper happened close to two years ago, when the Wiz still operated in New England; not long after, it declared bankruptcy and was bought by Cablevision Systems Corp., which closed the stores in Massachusetts. Dworsky hasn't had a bigger score since. But he still reads the ads, and, given the chance, he's ready to teach another retailer the same expensive lesson. "No one told them to do that," says Dworsky of the Wiz's advertising ploy. "But having done so, as a consumer, a consumer advocate, and a consumer educator, I expect them to live up to their offer." Dworsky's friends call him eccentric. His colleagues call him cheap. He doesn't mind. The way he sees it, he's the rare consumer advocate who happens to practice what he preaches. And even though most consumers wouldn't recognize his name, they have benefited for years from his tenacity. Working for the state, he led a crackdown on mattress retailers that advertised "sale" items that had never been sold at the "list" price. He halted "going-out-of-business sales" that relied on a steady stream of new merchandise. He punished retailers who put items on sale but failed to charge customers the lower prices at the register. He negotiated lawsuit settlements that returned more than $2 million to consumers. And even though he doesn't drive, he wrote the regulations for the new-car lemon law, which requires dealers to give customers a refund or a new car if a problem isn't corrected after a reasonable number of repair attempts. But what's even more remarkable about Dworsky is that he continues to fight for consumers even though he left state employment more than two years ago and now has no official job title. At 47, when many men are looking forward to retirement or going through a midlife crisis, Dworsky is full steam ahead with his one-man crusade for consumers. "The word `zealot' comes to mind," says Daniel Grabauskas, the state's director of consumer affairs. "That carries with it both good and bad connotations,but Edgar might be the number one zealot for consumers in Massachusetts." Advocates like Dworsky are rare these days. The poor pay, the long hours, and the constant uphill struggles have taken their toll. Fewer people are choosing full-time consumer advocacy work than in the 1960s, perhaps the heyday of consumer activism. That's probably partly because many basic consumer protections are already in place; the struggle today is over enforcing those protections and making sure consumers are aware of their rights. The work isn't as sexy as it once was. Even Ralph Nader seems to have lost some of his enthusiasm, spending his time on quixotic presidential campaigns rather than product recalls and pricing scams. Deirdre Cummings, the director of consumer programs for the Massachusetts Public Interest Research Group, says the shortage of advocates is surprising at a time when popular interest in consumer issues is rising. She notes that newspapers, local television stations, and national news shows like Dateline are devoting more resources to consumer stories than ever before. But when it comes to battling for legislation on Beacon Hill, Cummings says, she routinely finds herself outgunned by business lobbyists. In contrast with the mid-to-late 1980s, when a lot of consumer protection legislation was filed and some of it even passed, nowadays, she says, most advocates spend their time trying to keep existing laws on the books. In recent years, for example, there have been attempts to weaken the used-car lemon law and to allow banks to stop returning canceled checks to customers. And few new protections have been enacted: In the most recent session, a proposed ban on automated teller machine surcharges died in committee, despite unanimous support in the Senate, majority support in the House, and the backing of Acting Governor Paul Cellucci. Paula Lyons, the consumer reporter for WBZ-TV and a 20-year veteran of the beat, says she often has to spend time checking out groups that claim to advocate for consumers, because many are merely fronts for businesses. "There aren't as many consumer advocates today as there once were," she says. "And there are very few who have stayed at it over the years." Certainly consumers have their allies at the state attorney general's office and at the state's consumer affairs office, but officials in those offices tend to act more as referees between consumers and businesses than as advocates for consumers. Reflecting that balancing act, the full name of the state consumer affairs office is the Office of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation. And, since 1991, that office has been little more than a revolving door. Six different people have held the post of director, ostensibly the state's top consumer advocate. Of the five who have gone on to other positions, none are still working on consumer issues. One is a judge, one became a partner at a Boston law firm, one went to work for Xerox, and two have used the post as a steppingstone to a run for higher office this year. Dworsky is different. He spent 11 years, from 1985 to 1996, in consumer-related jobs, as a television reporter, a city official, and a state consumer official. For the past two years, he has been self-employed, using his skill at living cheaply to survive on the small advertising income he derives from advertising on his Web site, Consumerworld.org, and even that income is in doubt. For him, consumer activism is not a 9-to-5 job or a part-time hobby. It's a lifestyle.Whether it's a trip to Hawaii, a long-distance phone company, or just a can of tuna, Dworsky is fanatical about finding the best deal. He almost never splurges; it's not who he is. "I live below my means," he says proudly. At the door to his Charlestown condominium, visitors are asked to take off their shoes, to prevent wear on the rug and reduce cleaning costs. His closet is full of suits from Filene's Basement sales. He used to pay no more than $1.99 for a shirt, but inflation has pushed his limit up to $8. He still wears a shirt that he bought in 1982. Dworsky does his banking at US Trust and Salem Five Cents Savings Bank because they don't have ATM fees, and Salem Five offers free electronic banking. He likes to shop on the Internet these days, using a search engine that allows him to check prices at a number of discounters quickly. One of his two phones is served by MCI because his mother in Omaha has MCI, and that allows her to get a good Friends and Family rate. His other phone is assigned to Unidial, which offers long-distance service for 8.9 cents a minute, 24 hours a day, with six-second billing. If there's a way to get an item for less, Dworsky will find it. A 13-inch Sony color TV he bought last year initially cost $125, marked down from $249, at the Lechmere going-out-of-business sale. Later, when Lechmere cut prices another 20 percent, he used the price guarantee on his Capital One Gold Visa card to recoup the additional savings; he ended up paying just $99 for the set. Just recently, he picked up a $34.95 rebate form for CleanSweep 3 software, then found it on sale at Staplesfor $4.90. He mailed in the form and expects to pocket a $30 profit on the purchase. And when Continental Airlines in 1981 offered a round-trip ticket for $1.79 to the travelers who showed up at the airport dressed most like the places they wanted to go, Dworsky went as a pineapple -- and won a trip to Hawaii. Dworsky says he loves to hunt, not for deer or game, but for free merchandise. It was Stop & Shop, Dworsky says, that sparked his enthusiasm for the chase: In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the supermarket vowed that if the price on an item was higher than the advertised sale price, the customer would get the item free. "It became a challenge for me to go in and find mismarked items," Dworsky says. On one particularly memorable shopping trip, he and a friend snared $150 worth of free groceries, including canned hams, turkeys, and roasts. When he finds an item at a good price, Dworsky likes to buy in bulk: "I don't want to run out and have to pay full price." That's why he has 44 sticks of deodorant -- at least eight years' worth of perspiration control -- in his closet. Stored in his kitchen cabinet and his laundry room on a recent visit were 32 bags of Nestle's Morsels, 26 bags of chocolate sandwich cookies, 62 jars of barbecue sauce, 46 boxes of ziti, 38 one-pound boxes of pasta (he never pays more than $1 for 4 pounds of pasta), 72 cans of tuna, 32 cans of salmon, four cases of Green Giant sweet peas, 27 boxes of microwave popcorn, 35 bottles of grapefruit juice, 18 bottles of apple juice, 14 rolls of paper towels, and 20 boxes of Cascade dishwasher detergent. One friendswears Dworsky once bought a whopping number of Burger King Whoppers when they went on sale and froze the extras, though Dworsky says he can't recall doing that. Sometimes, though, the thrill of the chase overwhelms common sense. Dworsky bought a lot of pilchard, a kind of sardine that he planned to use as a cheaper substitute for tuna, when tuna prices skyrocketed in the 1970s. He still has several cans in his cabinet and can't seem to throw them out. He only recently tossed out several boxes of macaroni and cheese that he bought in the 1970s, before he discovered he was lactose intolerant. "Obviously, I'm not going to use some of these things," he says, pointing to a can of mushrooms from 1978. "But I can't throw them out, because it will mean acknowledging a loss." As he gets older, Dworsky is holding on to his passion for the deal. "If someone handed me a million dollars, people always ask whether I would do anything different," he says. "I don't think so. And I have to tell you, I think it's getting worse." Dworsky's obsession with consumer issues started early -- his favorite toy as a child in Queens, New York, was a cardboard supermarket, complete with tiny boxes of corn flakes -- and he thinks the syndrome may be partly inherited. He vividly remembers his grandfather buying huge quantities of Heinz beans and Dole pineapple juice when they went on sale. And his late father, who divorced his mother when Dworsky was 5, was just plain cheap, he says: At breakfast, Edgar was allowed only half a paper napkin, so the supply would last longer. Dworsky studied business administration and marketing at Northeastern University; after graduating in 1974, he worked briefly in customer relations and market research. He was fired from his second job for writing prank memos, but he didn't mind much; he was already beginning to identify more with the consumers he was researching than the manufacturer he was working for. After more than a year of being unemployed, Dworsky landed a job with the Boston Consumers' Council, today the Mayor's Office of Consumer Affairs and Licensing. He answered consumer questions and tried to mediate complaints, honing his skills as a consumer advocate. After two years, he shifted to part-time work so he could return to Northeastern for a law degree -- not so he could practice law but in order to better understand consumer law. In 1982, with his law degree in hand, he decided to take a crack at consumer reporting on television, though he didn't exactly have a TV polish. He wore glasses, talked with a thick New York accent, and had an odd sense of fashion: He bought boys' suits, because he was skinny enough to fit into them, and they were cheaper than men's suits. "I'm not a pretty face," Dworsky admits. But he was a "character," and he had a wealth of knowledge, so the producers of a new TV show called Look, on what was then WNEV-TV (Channel 7), gave him 10 minutes a day. Dworsky did well enough that when that show was canceled, its successor, New England Afternoon, picked him up. On one segment, Dworsky challenged an advertising claim by the Remington Products Co. that 99 percent of the owners of Remington electric shavers felt that the razor shaved as close as a blade. Under questioning by Dworsky, Remington's president, Victor Kiam, acknowledged that the claim was not based on survey research but on the flimsy evidence that only 1 percent of the shavers were returned. As Kiam fumed on camera, Dworsky interviewed several Remington owners who hadn't returned the razor but didn't think it shaved as close as a blade. "People ought to be able to believe what they see in ads," says Dworsky. "We shouldn't be living in a society where companies are lying to get people to buy their products." Dworsky's next job offer came from Paula Gold, who had been his boss when he worked in the attorney general's office as a Northeastern co-op student. Now heading the state's consumer affairs office, Gold told Dworsky he could pick his own title. He chose director of consumer education -- his first stop in a decade-long stint in state government dealing with consumer issues. Dworsky's specialty was drawing attention to the type of consumer issues that affect just about everyone in daily life. Perhaps his biggest peeve is companies that promise one thing and deliver another, whether it's zero-percent financing offers with hidden catches or the Benihana frozen shrimp dinner that he didn't think lived up to the picture on the package. "I call it pocketbook issues," says Dworsky. "For whatever reason, they catch people's attention." Gold, who now works for Plymouth Rock Assurance Co., of Boston, remembers Dworsky coming to her in 1986 with the idea of checking out the accuracy of "sell by" dates on supermarket meats. He came back with a provocative report suggesting that many supermarkets were exaggerating how long some products, particularly chicken, would stay fresh. What really impressed her, however, was how Dworsky could sell the story to the media. He insisted she hold a piece of smelly chicken right up to her nose at the press conference announcing the findings. The next day's Globe carried the picture and the story on the front page. "Everybody cares about those issues," Gold says. "No matter how much money you make, no one wants to get ripped off." Dworsky went from the consumer affairs office in the administration of Michael S. Dukakis to the attorney general's office under L. Scott Harshbarger; both politicians were Democrats who welcomed his style of consumer advocacy. Dworsky stayed on, once again in consumer affairs, under Governor William F. Weld, but says he found far less favor with the pro-business Republican administration. Twice, Weld suggested eliminating funding for the consumer affairs office, but, each time, Dworsky and his colleagues rallied supporters. They were helped by businesses like Star Market, Polaroid, Building 19, and T. J. Maxx, companies that Dworsky says valued an office that helped curb unscrupulous business practices. "I led a charmed life as a consumer advocate under both Dukakis and Harshbarger. I never remember a time when I was told not to pursue a particular case," Dworsky says. "But some of that began to rear its ugly head under Weld." Dworsky says he was told by his superiors that Weld had killed a report that Dworsky did three years ago, suggesting that Microsoft was using its market influence to control what retailers charged for its new Windows 95 software. Dworsky had surveyed retailers across the country and found no price competition; all of them were charging $89.95 for the software. Dworsky says the same thing happened this year with Windows 98. Weld, who now works at the law firm of McDermott, Will & Emery, says he has only a faint recollection of Dworsky and no memory at all of the Microsoft dispute. "I never heard of that," Weld says. Speaking publicly for the first time about his tenure under Weld, Dworsky says there was often pressure from administration officials to settle investigations quietly, out of the public eye. Many companies under investigation would hire lobbyists with close ties to the administration, he says, to make sure no press release was ever issued. The practice rankled Dworsky, for whom letting the public know had always been the priority. His frustration boiled over in early 1996, when Dworsky was negotiating a settlement with American Remodeling Inc., of Dallas, which handled home improvement work in Massachusetts on behalf of Sears, Roebuck & Co. The company had violated the state's contractor law from 1992 through 1995 by using unlicensed subcontractors and written contracts that failed to comply with state law. American Remodeling hired Mark Robinson, Weld's former chief of staff, to handle the negotiations. Not long after that, Dworsky says he was asked by one of his superiors at consumer affairs, who he knew had close ties to Robinson, what his bottom line was in the negotiations. "I basically refused to tell, for fear the whole negotiating process would be turned into a sham," Dworsky says. "For that, I was shown the door. That was viewed as a disloyal act on my part." Nancy Merrick, who was the director of consumer affairs at the time, says Dworsky was fired because of a streamlining effort at the agency. She denied there was any attempt to help Robinson's client. But Dworsky's colleagues on the negotiating team rallied behind Dworsky and pressed for a $2 million fine against American Remodeling. The company eventually settled for $650,000 but paid only $100,000 before going bankrupt. Dworsky hasn't had a title or an organization to call home for more than two years, but his consumer clout has barely diminished. He's been featured on ABC's 20-20 on how to shop for a long-distance phone company. NBC's Dateline took advantage of his food stockpile at home to illustrate a feature on manufacturers who subtly downsize their products without downsizing the price. Tuna cans, for example, went in a few years from containing 7 ounces of tuna to 6 ounces. Dworsky's Web site, an extensive array of news, tips, and shopping bargains, receives close to 1 million visitors a year -- not huge by Internet standards but not bad for a business operated out of a den. And, just recently, Dworsky was one of three consumer advocates whom state officials invited to the bargaining table as they tried to broker a deal with Massachusetts supermarkets on the testing of a controversial new electronic shelf-pricing system. The supermarkets hope the shelf-pricing system will do away with the need to mark prices on individual items in their stores, as state law now requires. Dworsky was included because he knows more about the issue than anyone else: He wrote the law the supermarkets hope to erase. In fact, on most pocketbook consumer issues, he is the closest thing the state has to an institutional memory. "What we don't have enough of in this state is people like Edgar," says Robert Sherman, who used to be Dworsky's boss at the attorney general's office and now works for a law firm in Boston. "There isn't anybody that has stepped up to replace him. In fact, many people have dropped off, but Edgar has stayed with it." The shelf-pricing battle typifies Dworsky's passion for the details of consumer life. It began in early 1986, when Dworsky was director of consumer education in the Dukakis administration. He urged the governor to veto a bill that would have exempted supermarkets from the state law requiring retailers to stamp prices on each item in their stores. He then negotiated compromise legislation that exempted a handful of supermarket items, including milk, eggs, and greeting cards, from the law. For supermarkets, the compromise left a bad aftertaste. They were stuck trying to make sure that the prices marked on 40,000 items matched the prices on store shelves and the prices at checkout scanners; it was a logistical nightmare. They wanted, as they still do, to scrap item pricing and replace it with electronic systems that would display prices at the shelf and be tied in by computer with checkout scanners. The systems, supermarket officials said, would eliminate pricing errors and free workers to serve customers. But each time the supermarkets made a push in the Legislature to do away with item pricing, Dworsky was there to block them. He considers item pricing an enormous consumer benefit: Survey research indicates, he says, that two-thirds of Massachusetts consumers learn the price of a can of beans by looking at the can, not at the shelf. Consumers also depend on item prices to compare prices and to verify that they are charged correctly at the checkout counter. Christopher Flynn, the executive director of the Massachusetts Food Association, which represents the state's supermarket industry, wanted Dworsky at the table for the current shelf-pricing negotiations, even though some of the group's members weren't crazy about the idea. "If he's not at the table, he esssentially will cause us all sorts of difficulty," says a resigned Flynn, who used to work with Dworsky on consumer issues at the attorney general's office. "He knows how to whip up consumer advocates and consumer reporters." After some tense negotiations, the supermarket industry has basically agreed to run a test of the shelf-pricing system, at a handful of stores, on the items in those stores that don't need to be marked individually. It wasn't what the supermarkets wanted -- indeed, the stores had rejected a similar test years ago -- but they are hoping that the test will succeed, and then translate into action on Beacon Hill. Flynn doesn't expect Dworsky ever to go along with ending item pricing. He says it's a perfect example of how Dworsky's mistrust of business always takes him to an extreme position. Flynn says consumers only want to pay the correct price for an item, while Dworsky favors a costly, complicated system that will lead to mismarked items that he can get for free. "He likes to set up laws the way he likes to shop," Flynn says. "Well, let me tell you, most people don't shop the way Edgar shops." That's certainly true. But Dworsky thinks his concerns are valid and are shared by most consumers. "I always say there's a little bit of Edgar in everyone," he says. "How much you admit to, and how much you practice, is another matter.